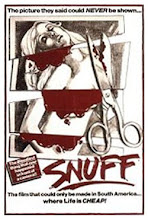

“The Film That Could Only Be Made in South America… Where Life Is Cheap!” touts the theatrical adline to Snuff, a low-budget production that continues to create controversy thirty-three years after its initial release. Despite the film’s relative obscurity, Snuff--the product of an ingenious marketing ploy by an opportunistic film producer--has secured itself a place in cinematic history, as well as contributing an incendiary urban legend to America’s rich folklore. Although the subject has only occasionally made the news in recent years, “snuff films” became a scapegoat for the sins of a narcissistic, jaded society during the 1970s and 1980s, the presumed culmination of our being exposed to excessive violence in the media and the arts.

So what is a snuff film? The Random House Dictionary, in a relatively new entry, defines a snuff movie as “a pornographic film that shows an actual murder of one of the performers, as at the end of a sadistic act.” It also states in a secondary definition that “snuff films” are synonymous with “splatter films,” an egregious error in and of itself. The American Heritage Dictionary offers a similarly erroneous definition, sans the splatter film connection. For reasons of clarity and propriety, a proper definition of snuff should instead be based on the film that single-handedly popularized the concept and introduced it into the public lexicon:

Snuff film (noun) Any film that depicts the premeditated onscreen death of one or more of its actors without their knowledge or consent, which is produced specifically for the sole intention of profiting from its distribution.

Although the film in question may be pornographic, this has never been part of the essential criteria as some references cite, as the film which defines snuff is not sexually explicit. Furthermore, profit is the ultimate objective. An exorbitant price tag compensates for the extremely limited distribution through black market channels, willingly paid for by affluent clients with jaded interests. Finally, “splatter films” are legitimate, perfectly legal productions that rely on staged bloodletting for scenes of gratuitous violence, leaving no room for association with snuff, which eschews the use of special effects by actually sacrificing its cast. (Most modern horror films contain a certain amount of gratuity, so the cinematic use of the term “splatter” has become virtually obsolete except in a historical context.)

There are other types of cinema that are often associated--or even conflated--with snuff films, despite the fact that they fall short of the necessary criteria. The most popular of these is known as the “shockumentary,” a brand of sensational, exploitive pseudo-documentary that often collects “found” footage of death and dismemberment from other sources, including newsreels or home video recordings that unintentionally capture such shocking images. (Often, these tasteless productions—such as the infamous Faces of Death series--pad out these scraps of genuine carnage with special effects-laden “fakes” and cruel scenes of real-life animal butchery.) Although this type of “entertainment” has played grindhouses since the 1930s, they became prominent fixtures at drive-ins throughout the 1960s and 1970s thanks to an Italian production released worldwide as Mondo Cane [A Dog’s Life] (1962). (Because of this film’s box-office success, and the slough of similarly titled films in its wake, shockumentaries are also referred to as “mondo” films.) Since shockumentaries occasionally depict real scenes of death—even though they weren’t specifically produced for the film and with criminal intent—their popularity seems to give snuff films validity by showing that there very well could be a demand for such sadistic fare, however limited.

Another misconception is that video recordings made by serial killers for the sole purpose of documenting their disturbing deeds qualify as snuff. On the contrary, these films—known as “trophy” films, with which the psychopathic personality can use to relive the moments of their sadistic crimes—are never made with a financial gain in mind, so they are considered by criminologists a separate animal altogether.

Most people are aghast when they first learn about snuff films, and may ask, “How could somebody do such a thing? What is being done to bring to justice those individuals responsible these black market atrocities?” Truth be told, very little is being done about them, simply because there is no evidence that they even exist. Not to say that such a thing as a snuff film isn’t possible. Still, when one takes into account the complicated logistics of creating and distributing such a product, along with the lack of verifiable proof that any such film has ever been produced and sold, snuff films—as defined above—are improbable. So why has so much fuss been made about snuff films, if their very existence has never been confirmed? Historians can lay the blame entirely at the feet of the aforementioned film Snuff.

In 1972, film producer Allan Shackleton bought the world distribution rights to a low budget film called The Slaughter (1971). Made by sexploitation filmmakers Michael and Roberta Findlay, this thinly veiled take on the Manson family’s well-publicized killing spree had a limited theatrical release before being shelved due to poor box-office returns. Shackleton desperately needed a creative approach with which to market the film successfully, so he decided that the best publicity he could muster was through controversy.

In 1975, Shackleton put together a guerilla cast and crew with which to shoot a new five-minute finale. This new footage depicted what is supposed to be one of the original actresses in a candid moment following the final take. After she makes time with the purported director of the film, the remaining crew members descend upon her with cameras rolling, capturing her alleged final moments. The viewer is forced to watch as the demented filmmaker tortures and eventually eviscerates the unwary thespian, conveniently completing his unholy mission only seconds before the camera runs out of film stock. Anyone who has seen this footage remains unconvinced by the dubious proceedings: There is no continuity whatsoever between the two films, the performances are poor, and the dimestore special effects even worse. But this didn’t deter Shackleton, as the whole point was to get ticket buyers into the theatre; whatever happened after that was immaterial. Even the opportunistic director, though, didn’t realize the impact his deception would have on this country… and this is where snuff went from being an obscure concept to a nationwide panic and an indefatigable urban legend.

Bearing a new title alongside ambiguous claims that it was “The Picture They Said Could Never Be Shown,” press releases and advertisements implied that, unlike other horror films, the carnage caught on camera was not faked. Shackleton then proceeded to distribute bogus newspaper clippings detailing the efforts of one “Vincent Sheehan,” the head of a fictional organization called Citizens for Decency, and his relentless crusade against the film in question. Not surprisingly, genuine groups bought into the prefabricated hysteria, and before long every theatre showing the film was festooned with picket lines protesting the public display of what they assumed to be a real-life atrocity. Almost overnight, this threadbare production made national headlines, whilst establishing the groundwork for a myth that still persists to this very day.

Within a few months of its controversial release, authorities looked into the possible illegality of the film, but found the content so laughable as to not warrant any further investigation. Surprisingly, their official statements exposing the rumors to be false did not deter the public outcry, as word of mouth continued, perpetuated by individuals who had never even seen the film, or questioned its authenticity. Even after the film had long worn out its welcome, the furor surrounding the existence of snuff cinema endured. This cinematic bogeyman has inspired innumerable films and books, and has become so entrenched in America’s psyche that even today concerned citizens cite snuff as being a billion-dollar industry lurking just beneath the radar of the law. Despite countless, concerted efforts to unearth a bona fide snuff film, authorities have resigned this cinematic phenomenon—as defined by the film that inspired the concept--to the domain of urban legends.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

+One-Sheet.jpg)

+One-Sheet.jpg)

+One-Sheet.jpg)

Scott,

ReplyDeleteGreat essay, I found your essay entertaining and informing. I thought I new a little about snuffs film, but I stand corrected and now I'm am thoroughly informed.

Chris

Nicely done revision. I liked how you contrasted snuff with other similar genres.

ReplyDelete