Thursday, March 12, 2009

Sunday, March 8, 2009

Reflecting on the First Quarter

My name is Scott Aaron Stine, and I am a native resident of Snohomish County. I have spent the entirety of my adult life as a semi-professional writer and artist, and have sidelined as a fairly accomplished composer and musician. As a writer, I have several books and a fair number of short stories (and even a few articles) to my credit. (Don’t worry if you haven’t heard of me; it is doubtful that you have ever stumbled across my work, considering the obscure publications in which they have seen print.) As of late 2008, I decided to finally go to college in order to obtain a degree in Literature and/or Fine Arts, as my professional life has been a real struggle these last few years. With the validation of a degree, and the additional knowledge and experience I know college has to offer, I hope to change this in the years to come.

College—and, in particular, the English 98 course—has proven to be an invaluable experience for me. Not only has it met all of my expectations so far, it has also vindicated my belief that no one is ever too old for personal growth.

Writing as a skill and an art form is—as it should be—a never-ending process. There is always room to improve upon what one already knows, as well as to broaden ones voice. The writing process itself is key in strengthening ones proficiency—it cannot be overstated the importance of exercising ones skills regularly—but other factors also contribute to a writer’s facility to mold the written word into something exceptional and unique. The act of reading, everything and anything, is inarguably beneficial. Familiarity with what past wordsmiths have already put to paper gives a writer an edge, expands ones lexicon, and exposes one to an endless variety of voices with which to explore. Just as important is life experience itself, as this grounds our knowledge with an intimate perspective of the world surrounding us. These are some of the reasons why I, as a writer, have found college to be such a boon.

Unlike a high school English class, where one primarily learns the basic rules of grammar and composition by rote, a college course such as this requires the writer to constructively apply this knowledge and expand ones creative potential. The steadfast exercises force the writer to endeavor outside of ones comfort zone, avoiding the ruts formed by such boundaries, and elude stagnation. The emphasis on group interaction allows the writer to hear firsthand how a diverse group of people views and interprets ones work. This discussion forces the writer to look at ones own output more objectively, which is vital if one wishes to hone their skills and strengthen ones voice.

Due to certain inherent demands of this avocation, writers tend to be fairly sedentary creatures. Seclusion often comes with the territory, so the synergistic atmosphere of a classroom is advantageous when one has practiced their craft alone for any considerable length of time. This particular class not only allows for some much needed feedback from peers, it also gives the student an opportunity to expand ones worldview through Service Learning. By placing the student in a position that they may never have done on their own volition, the burgeoning writer finds oneself interacting with people from other walks of life with which one may be unfamiliar. Experience like this cannot simply be obtained from books, as you are seeing it filtered through the eyes of another person’s worldview; intimacy is crucial in expanding ones grasp of the human condition. So, I am extremely thankful to have been a part of this internship, as it has had a profound impact on me as an individual, and thus had an equally significant impact on me as a writer.

For this E-Portfolio, I have included four pieces produced within this class. For a piece that represents my ability to take a piece through the writing process, I chose my first MWA, a comparison/contrast paper entitled “Halloween: John Carpenter vs. Rob Zombie.” For a piece that demonstrates my ability to write effectively, I chose my second MWA, a definition essay entitled “Snuff: The Final Cut.” For a piece that demonstrates my ability to write analytically, I chose my third MWA, an argument essay entitled “The Satanic Conspiracy: Witch Hunting in the Twentieth Century and Beyond.” For my writer’s choice entry, I chose our very first assignment, the “Inventory of Being” essay with which we used to introduce ourselves to our instructor and classmates. I have also included a short humorous piece entitled “But I Digress…” in order to lighten the mood set by the progressively darker MWAs.

So, if you have some spare time, sit back, peruse the following examples of my college writing, and feel free to drop me a line with any feedback you may have. Enjoy!

College—and, in particular, the English 98 course—has proven to be an invaluable experience for me. Not only has it met all of my expectations so far, it has also vindicated my belief that no one is ever too old for personal growth.

Writing as a skill and an art form is—as it should be—a never-ending process. There is always room to improve upon what one already knows, as well as to broaden ones voice. The writing process itself is key in strengthening ones proficiency—it cannot be overstated the importance of exercising ones skills regularly—but other factors also contribute to a writer’s facility to mold the written word into something exceptional and unique. The act of reading, everything and anything, is inarguably beneficial. Familiarity with what past wordsmiths have already put to paper gives a writer an edge, expands ones lexicon, and exposes one to an endless variety of voices with which to explore. Just as important is life experience itself, as this grounds our knowledge with an intimate perspective of the world surrounding us. These are some of the reasons why I, as a writer, have found college to be such a boon.

Unlike a high school English class, where one primarily learns the basic rules of grammar and composition by rote, a college course such as this requires the writer to constructively apply this knowledge and expand ones creative potential. The steadfast exercises force the writer to endeavor outside of ones comfort zone, avoiding the ruts formed by such boundaries, and elude stagnation. The emphasis on group interaction allows the writer to hear firsthand how a diverse group of people views and interprets ones work. This discussion forces the writer to look at ones own output more objectively, which is vital if one wishes to hone their skills and strengthen ones voice.

Due to certain inherent demands of this avocation, writers tend to be fairly sedentary creatures. Seclusion often comes with the territory, so the synergistic atmosphere of a classroom is advantageous when one has practiced their craft alone for any considerable length of time. This particular class not only allows for some much needed feedback from peers, it also gives the student an opportunity to expand ones worldview through Service Learning. By placing the student in a position that they may never have done on their own volition, the burgeoning writer finds oneself interacting with people from other walks of life with which one may be unfamiliar. Experience like this cannot simply be obtained from books, as you are seeing it filtered through the eyes of another person’s worldview; intimacy is crucial in expanding ones grasp of the human condition. So, I am extremely thankful to have been a part of this internship, as it has had a profound impact on me as an individual, and thus had an equally significant impact on me as a writer.

For this E-Portfolio, I have included four pieces produced within this class. For a piece that represents my ability to take a piece through the writing process, I chose my first MWA, a comparison/contrast paper entitled “Halloween: John Carpenter vs. Rob Zombie.” For a piece that demonstrates my ability to write effectively, I chose my second MWA, a definition essay entitled “Snuff: The Final Cut.” For a piece that demonstrates my ability to write analytically, I chose my third MWA, an argument essay entitled “The Satanic Conspiracy: Witch Hunting in the Twentieth Century and Beyond.” For my writer’s choice entry, I chose our very first assignment, the “Inventory of Being” essay with which we used to introduce ourselves to our instructor and classmates. I have also included a short humorous piece entitled “But I Digress…” in order to lighten the mood set by the progressively darker MWAs.

So, if you have some spare time, sit back, peruse the following examples of my college writing, and feel free to drop me a line with any feedback you may have. Enjoy!

Preface to

Halloween: John Carpenter vs. Rob Zombie

Since this was to be my first Major Writing Assignment of my first quarter attending college, I decided to write about something with which I was already comfortable, namely film. Since high school, I have written extensively about cinema, and have penned countless film reviews and articles, so it seemed a natural choice. Since this was a contrast/comparison paper, it seemed like a perfect forum to compare a classic horror film with its modern day counterpart. Not only could I illustrate the differences between production values and style, I could also explore the major themes, and how they reflect the culture and time period in which they were filmed. In addition, I did not want to simply show how one was inferior or superior to the other, since in many ways these values are entirely subjective, so I decided to pick a film whose remake displayed some merit as well, but worked on a much different level. So, I took the film that officially kick-started the slasher genre, and the remake filmed by a shock rocker-turned filmmaker.

Prior to starting college this January, I had spent several years writing only sporadically, and had received practically no feedback on what little I did pen. Being that this was the first MWA of the quarter, the rough draft of this piece reflects it. Working on automatic, I had fallen into several stylistic ruts, and my predisposition to run-on sentences had again gotten out of control. Since I had been writing specifically to niche audiences for quite a few years—cinephiles in particular—I had forgotten how to reach a general audience. The feedback I received on this essay brought to light both of these issues, but hopefully my rewrite succeeds in rectifying this.

Prior to starting college this January, I had spent several years writing only sporadically, and had received practically no feedback on what little I did pen. Being that this was the first MWA of the quarter, the rough draft of this piece reflects it. Working on automatic, I had fallen into several stylistic ruts, and my predisposition to run-on sentences had again gotten out of control. Since I had been writing specifically to niche audiences for quite a few years—cinephiles in particular—I had forgotten how to reach a general audience. The feedback I received on this essay brought to light both of these issues, but hopefully my rewrite succeeds in rectifying this.

Halloween: John Carpenter vs. Rob Zombie

In recent years, it has become increasingly popular for Hollywood to produce remakes of classic (and not-so-classic) films. Such a production is a reflection of Hollywood’s lack of originality, or a studio’s desire to update a property or franchise so that it will be more receptive to a younger generation, or a filmmaker’s sincere attempt at revisioning a film that inspired them. Whether it is ultimately a financial or artistic decision, this practice has caused much controversy among filmgoers, casual and serious alike. One such film, at least among fans of the horror genre, is Halloween.

Originally released in 1978, this low-budget film not only inspired an entire horror sub-genre—the slasher film—it also inspired a big-budget remake that was released twenty-nine years later. Although the two share the same source material, both films are markedly different, especially in respect to their production values, their sense of aesthetics, and the underlying thematic elements.

In his third outing as director, John Carpenter (1948-) took his first stab at the horror film genre, Halloween, which cost the studio $320,000 when all was said and done. Despite the modest production values, the film grossed over forty-seven million dollars in the United States alone, and proved to be the highest grossing independent film made up to the time of its release.

Although technically competent, the film bears many earmarks of a low budget feature. Even though the action takes place in the fictitious town of Haddonfield, Illinois, the backdrop is obviously Southern California, as the occasional palm tree attests. Short on the cash with which to hire recognizable celebrities, the cast is instead comprised of B-film veterans and virtual unknowns. Cinematography that would rely on tracked dollies in more commercial efforts is instead the product of handheld, almost cinema veríte-style camerawork. Special effects are kept to a bare minimum. A modest film, the same couldn’t be said for the remake it inspired.

In what would be his third directorial outing as well, Rob Zombie née Robert Cummings (1965-) offered his distinct revisioning of Carpenter’s classic slasher film. It was made on a healthy Hollywood budget of twenty-million dollars, a far cry from the original, which was made on less than 1/60 of the remake’s budget. Zombie’s updating grossed around sixty-million dollars in the United States; although the profits were enough to garner the announcement of a forthcoming sequel, the profit margin wasn’t nearly as impressive as the original’s unprecedented success.

Inherently far more professional that Carpenter’s film, Zombie makes an honest attempt to retain the distinctly 70s feel of the original by mimicking it on a technical level. Again, the film was shot in South California, even though the action took place in the mid-west. Despite the money at Zombie’s disposal, he purposely chose to populate his cast with B-film veterans and virtual unknowns. (Among the seasoned actors were many names easily recognized by fans of 1970s drive-in fodder.) One of the most notable differences is the heavy use of special effects; with an effects budget that far surpasses the cost of its predecessor’s entire production, Zombie spared no effort in making the murders as gruesome and realistic as the ratings board would allow; whereas most of the violence in Carpernter’s version was concealed in shadow, Zombie kept the carnage well-lit and always within sight of the camera’s unflinching eye.

Production values aside, aesthetics are an important aspect of both films. The major factor behind the original film’s success is the presence of the director’s distinct style. Although the material would have proved pedestrian in the hands of a less talented filmmaker, Carpenter’s unique choreography creates a building momentum of suspense punctuated by abrupt shocks. Owing much to the likes of Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks, the pacing is terse, with tension generated from the use of nearly subliminal cues, both visual and musical. The score verges on minimalism, its 5/4 time signature entirely composed by a piano and a keyboard vying for dominance with only a handful of notes at their collective disposal.

The sequel, though, is a much different animal. Knowing that he was incapable of recreating the level of suspense found in the original, Zombie instead drew upon the strengths he displayed in his previous film The Devil’s Rejects (2005) by depicting the proceedings in a straightforward, brutally realistic manner. (As mentioned earlier, the liberal effects budget allowed for such excesses.) The remake relies far more on outright shocks than carefully orchestrated tension, which—intentions aside—seems to reverberate more with today’s jaded filmgoers.

As disturbing as the violence is in both films, what wormed their way under most viewers’ skin are the themes. In the original, antagonist Michael Myers is portrayed as a faceless, emotionless husk whose bloodlust is his sole purpose for existing. Michael, as a child, is seen only in a brief introduction, with most of the film’s running time devoted to his crimes as an adult. No motives are offered for his compulsions, no childhood trauma is evoked, his inexcusable actions beyond all rational explanation. He is the epitome of evil, as a society might have defined it. Carpenter endeavored to create a character with whom people could not identify, and in this sense he succeeded.

When Halloween was released in 1978, the United States was in the clutches of a growing phenomenon of serial murders. Citizens were more than ever being preyed upon by killers unknown, who were driven by their twisted psyches as opposed to personal gain. Psychopaths like the Zodiak Killer and Son of Sam even went so far as to gloat to authorities about their bloodied exploits whilst eluding capture. Although some would eventually be caught, others remained anonymous. In this way, Halloween reflected this mass anxiety: Michael Myers symbolized the country’s futile attempt to put a face to the name, and their fears of a bogeyman that preyed upon the unwary and unsuspecting.

Thirty years later, serial killers are no longer beyond our general scope of understanding. With the growing art and science of criminal profiling, we have since put faces to many of the once unthinkable crimes. These killers are more often than not the product of childhood abuse, their actions the direct result of extreme conditioning.

In Zombie’s 2007 remake, Michael Myers is no longer a motiveless killer, and the mask he wears no longer reflects the utter lack of identity, but symbolizes the harsh cruelty of a life gone horribly wrong. Half of the film is devoted to the years preceding the inevitable All Hallow’s Eve massacre. We see the dysfunctional family that spawned Michael, and the progressive deterioration of personality while he is institutionalized for the murders he committed during his youth. As we have learned about most serial killers in the last three decades, he is no longer an enigmatic aberration, but a victim whose bloodlust is fueled by personal demons and an untethered id. Although Zombie’s end result of the character seems much like Carpenter’s, we are given the chance to identify with Michael Myers early on, which in some ways makes his character even more frightening.

In closing, the original Halloween and its 2007 remake are disparate visions of the same source material by two very unique, talented voices. Despite a few similarities in tone, the differences are marked, especially when it comes to the films’ sense of aesthetics and the thematic elements they wish to convey. Both are the products of their times, and so they appeal to two very different generations of filmgoers. As such, the controversy will continue between the two camps of fans that have supported these efforts.

Originally released in 1978, this low-budget film not only inspired an entire horror sub-genre—the slasher film—it also inspired a big-budget remake that was released twenty-nine years later. Although the two share the same source material, both films are markedly different, especially in respect to their production values, their sense of aesthetics, and the underlying thematic elements.

In his third outing as director, John Carpenter (1948-) took his first stab at the horror film genre, Halloween, which cost the studio $320,000 when all was said and done. Despite the modest production values, the film grossed over forty-seven million dollars in the United States alone, and proved to be the highest grossing independent film made up to the time of its release.

Although technically competent, the film bears many earmarks of a low budget feature. Even though the action takes place in the fictitious town of Haddonfield, Illinois, the backdrop is obviously Southern California, as the occasional palm tree attests. Short on the cash with which to hire recognizable celebrities, the cast is instead comprised of B-film veterans and virtual unknowns. Cinematography that would rely on tracked dollies in more commercial efforts is instead the product of handheld, almost cinema veríte-style camerawork. Special effects are kept to a bare minimum. A modest film, the same couldn’t be said for the remake it inspired.

In what would be his third directorial outing as well, Rob Zombie née Robert Cummings (1965-) offered his distinct revisioning of Carpenter’s classic slasher film. It was made on a healthy Hollywood budget of twenty-million dollars, a far cry from the original, which was made on less than 1/60 of the remake’s budget. Zombie’s updating grossed around sixty-million dollars in the United States; although the profits were enough to garner the announcement of a forthcoming sequel, the profit margin wasn’t nearly as impressive as the original’s unprecedented success.

Inherently far more professional that Carpenter’s film, Zombie makes an honest attempt to retain the distinctly 70s feel of the original by mimicking it on a technical level. Again, the film was shot in South California, even though the action took place in the mid-west. Despite the money at Zombie’s disposal, he purposely chose to populate his cast with B-film veterans and virtual unknowns. (Among the seasoned actors were many names easily recognized by fans of 1970s drive-in fodder.) One of the most notable differences is the heavy use of special effects; with an effects budget that far surpasses the cost of its predecessor’s entire production, Zombie spared no effort in making the murders as gruesome and realistic as the ratings board would allow; whereas most of the violence in Carpernter’s version was concealed in shadow, Zombie kept the carnage well-lit and always within sight of the camera’s unflinching eye.

Production values aside, aesthetics are an important aspect of both films. The major factor behind the original film’s success is the presence of the director’s distinct style. Although the material would have proved pedestrian in the hands of a less talented filmmaker, Carpenter’s unique choreography creates a building momentum of suspense punctuated by abrupt shocks. Owing much to the likes of Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks, the pacing is terse, with tension generated from the use of nearly subliminal cues, both visual and musical. The score verges on minimalism, its 5/4 time signature entirely composed by a piano and a keyboard vying for dominance with only a handful of notes at their collective disposal.

The sequel, though, is a much different animal. Knowing that he was incapable of recreating the level of suspense found in the original, Zombie instead drew upon the strengths he displayed in his previous film The Devil’s Rejects (2005) by depicting the proceedings in a straightforward, brutally realistic manner. (As mentioned earlier, the liberal effects budget allowed for such excesses.) The remake relies far more on outright shocks than carefully orchestrated tension, which—intentions aside—seems to reverberate more with today’s jaded filmgoers.

As disturbing as the violence is in both films, what wormed their way under most viewers’ skin are the themes. In the original, antagonist Michael Myers is portrayed as a faceless, emotionless husk whose bloodlust is his sole purpose for existing. Michael, as a child, is seen only in a brief introduction, with most of the film’s running time devoted to his crimes as an adult. No motives are offered for his compulsions, no childhood trauma is evoked, his inexcusable actions beyond all rational explanation. He is the epitome of evil, as a society might have defined it. Carpenter endeavored to create a character with whom people could not identify, and in this sense he succeeded.

When Halloween was released in 1978, the United States was in the clutches of a growing phenomenon of serial murders. Citizens were more than ever being preyed upon by killers unknown, who were driven by their twisted psyches as opposed to personal gain. Psychopaths like the Zodiak Killer and Son of Sam even went so far as to gloat to authorities about their bloodied exploits whilst eluding capture. Although some would eventually be caught, others remained anonymous. In this way, Halloween reflected this mass anxiety: Michael Myers symbolized the country’s futile attempt to put a face to the name, and their fears of a bogeyman that preyed upon the unwary and unsuspecting.

Thirty years later, serial killers are no longer beyond our general scope of understanding. With the growing art and science of criminal profiling, we have since put faces to many of the once unthinkable crimes. These killers are more often than not the product of childhood abuse, their actions the direct result of extreme conditioning.

In Zombie’s 2007 remake, Michael Myers is no longer a motiveless killer, and the mask he wears no longer reflects the utter lack of identity, but symbolizes the harsh cruelty of a life gone horribly wrong. Half of the film is devoted to the years preceding the inevitable All Hallow’s Eve massacre. We see the dysfunctional family that spawned Michael, and the progressive deterioration of personality while he is institutionalized for the murders he committed during his youth. As we have learned about most serial killers in the last three decades, he is no longer an enigmatic aberration, but a victim whose bloodlust is fueled by personal demons and an untethered id. Although Zombie’s end result of the character seems much like Carpenter’s, we are given the chance to identify with Michael Myers early on, which in some ways makes his character even more frightening.

In closing, the original Halloween and its 2007 remake are disparate visions of the same source material by two very unique, talented voices. Despite a few similarities in tone, the differences are marked, especially when it comes to the films’ sense of aesthetics and the thematic elements they wish to convey. Both are the products of their times, and so they appeal to two very different generations of filmgoers. As such, the controversy will continue between the two camps of fans that have supported these efforts.

Preface to

Snuff Films: The Final Cut

Over the years, I have written a great many articles about snuff films, have been interviewed on the subject, and have been consulted on this pervasive myth for several television documentaries. So, being something of a recognized “authority” on the subject, composing a college paper defining snuff films would be a cinch, a pushover, a walk in the park, and as easy as apple pie. Right? To some extent, I made this assumption as well, but…

With this paper, I faced several challenges: Firstly, to distill the information so the pertinent information could fit into the allotted space; and, secondly, to write it to an audience who was unfamiliar with the concept or term, as my audience in the past was already well-versed in the basics. The fact that my advisor and most of my peers were unacquainted with the snuff film phenomenon was ultimately invaluable, as it helped me to (eventually) define it clearly and objectively whilst avoiding the dangerous assumption that the readers were cinephiles. (I faced this problem with my first essay, but it became far more apparent with this piece.) Because of numerous misconceptions, I also found myself succinctly defining several other cinematic subgenres, including “shockumentaries” and splatter films, which were also not part of the average person’s lexicon.

Of my three MWAs in English 098, this was the one that would see the most rewrites, but in the long run, it was worth it.

With this paper, I faced several challenges: Firstly, to distill the information so the pertinent information could fit into the allotted space; and, secondly, to write it to an audience who was unfamiliar with the concept or term, as my audience in the past was already well-versed in the basics. The fact that my advisor and most of my peers were unacquainted with the snuff film phenomenon was ultimately invaluable, as it helped me to (eventually) define it clearly and objectively whilst avoiding the dangerous assumption that the readers were cinephiles. (I faced this problem with my first essay, but it became far more apparent with this piece.) Because of numerous misconceptions, I also found myself succinctly defining several other cinematic subgenres, including “shockumentaries” and splatter films, which were also not part of the average person’s lexicon.

Of my three MWAs in English 098, this was the one that would see the most rewrites, but in the long run, it was worth it.

Snuff Films: The Final Cut

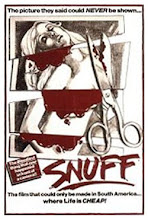

“The Film That Could Only Be Made in South America… Where Life Is Cheap!” touts the theatrical adline to Snuff, a low-budget production that continues to create controversy thirty-three years after its initial release. Despite the film’s relative obscurity, Snuff--the product of an ingenious marketing ploy by an opportunistic film producer--has secured itself a place in cinematic history, as well as contributing an incendiary urban legend to America’s rich folklore. Although the subject has only occasionally made the news in recent years, “snuff films” became a scapegoat for the sins of a narcissistic, jaded society during the 1970s and 1980s, the presumed culmination of our being exposed to excessive violence in the media and the arts.

So what is a snuff film? The Random House Dictionary, in a relatively new entry, defines a snuff movie as “a pornographic film that shows an actual murder of one of the performers, as at the end of a sadistic act.” It also states in a secondary definition that “snuff films” are synonymous with “splatter films,” an egregious error in and of itself. The American Heritage Dictionary offers a similarly erroneous definition, sans the splatter film connection. For reasons of clarity and propriety, a proper definition of snuff should instead be based on the film that single-handedly popularized the concept and introduced it into the public lexicon:

Snuff film (noun) Any film that depicts the premeditated onscreen death of one or more of its actors without their knowledge or consent, which is produced specifically for the sole intention of profiting from its distribution.

Although the film in question may be pornographic, this has never been part of the essential criteria as some references cite, as the film which defines snuff is not sexually explicit. Furthermore, profit is the ultimate objective. An exorbitant price tag compensates for the extremely limited distribution through black market channels, willingly paid for by affluent clients with jaded interests. Finally, “splatter films” are legitimate, perfectly legal productions that rely on staged bloodletting for scenes of gratuitous violence, leaving no room for association with snuff, which eschews the use of special effects by actually sacrificing its cast. (Most modern horror films contain a certain amount of gratuity, so the cinematic use of the term “splatter” has become virtually obsolete except in a historical context.)

There are other types of cinema that are often associated--or even conflated--with snuff films, despite the fact that they fall short of the necessary criteria. The most popular of these is known as the “shockumentary,” a brand of sensational, exploitive pseudo-documentary that often collects “found” footage of death and dismemberment from other sources, including newsreels or home video recordings that unintentionally capture such shocking images. (Often, these tasteless productions—such as the infamous Faces of Death series--pad out these scraps of genuine carnage with special effects-laden “fakes” and cruel scenes of real-life animal butchery.) Although this type of “entertainment” has played grindhouses since the 1930s, they became prominent fixtures at drive-ins throughout the 1960s and 1970s thanks to an Italian production released worldwide as Mondo Cane [A Dog’s Life] (1962). (Because of this film’s box-office success, and the slough of similarly titled films in its wake, shockumentaries are also referred to as “mondo” films.) Since shockumentaries occasionally depict real scenes of death—even though they weren’t specifically produced for the film and with criminal intent—their popularity seems to give snuff films validity by showing that there very well could be a demand for such sadistic fare, however limited.

Another misconception is that video recordings made by serial killers for the sole purpose of documenting their disturbing deeds qualify as snuff. On the contrary, these films—known as “trophy” films, with which the psychopathic personality can use to relive the moments of their sadistic crimes—are never made with a financial gain in mind, so they are considered by criminologists a separate animal altogether.

Most people are aghast when they first learn about snuff films, and may ask, “How could somebody do such a thing? What is being done to bring to justice those individuals responsible these black market atrocities?” Truth be told, very little is being done about them, simply because there is no evidence that they even exist. Not to say that such a thing as a snuff film isn’t possible. Still, when one takes into account the complicated logistics of creating and distributing such a product, along with the lack of verifiable proof that any such film has ever been produced and sold, snuff films—as defined above—are improbable. So why has so much fuss been made about snuff films, if their very existence has never been confirmed? Historians can lay the blame entirely at the feet of the aforementioned film Snuff.

In 1972, film producer Allan Shackleton bought the world distribution rights to a low budget film called The Slaughter (1971). Made by sexploitation filmmakers Michael and Roberta Findlay, this thinly veiled take on the Manson family’s well-publicized killing spree had a limited theatrical release before being shelved due to poor box-office returns. Shackleton desperately needed a creative approach with which to market the film successfully, so he decided that the best publicity he could muster was through controversy.

In 1975, Shackleton put together a guerilla cast and crew with which to shoot a new five-minute finale. This new footage depicted what is supposed to be one of the original actresses in a candid moment following the final take. After she makes time with the purported director of the film, the remaining crew members descend upon her with cameras rolling, capturing her alleged final moments. The viewer is forced to watch as the demented filmmaker tortures and eventually eviscerates the unwary thespian, conveniently completing his unholy mission only seconds before the camera runs out of film stock. Anyone who has seen this footage remains unconvinced by the dubious proceedings: There is no continuity whatsoever between the two films, the performances are poor, and the dimestore special effects even worse. But this didn’t deter Shackleton, as the whole point was to get ticket buyers into the theatre; whatever happened after that was immaterial. Even the opportunistic director, though, didn’t realize the impact his deception would have on this country… and this is where snuff went from being an obscure concept to a nationwide panic and an indefatigable urban legend.

Bearing a new title alongside ambiguous claims that it was “The Picture They Said Could Never Be Shown,” press releases and advertisements implied that, unlike other horror films, the carnage caught on camera was not faked. Shackleton then proceeded to distribute bogus newspaper clippings detailing the efforts of one “Vincent Sheehan,” the head of a fictional organization called Citizens for Decency, and his relentless crusade against the film in question. Not surprisingly, genuine groups bought into the prefabricated hysteria, and before long every theatre showing the film was festooned with picket lines protesting the public display of what they assumed to be a real-life atrocity. Almost overnight, this threadbare production made national headlines, whilst establishing the groundwork for a myth that still persists to this very day.

Within a few months of its controversial release, authorities looked into the possible illegality of the film, but found the content so laughable as to not warrant any further investigation. Surprisingly, their official statements exposing the rumors to be false did not deter the public outcry, as word of mouth continued, perpetuated by individuals who had never even seen the film, or questioned its authenticity. Even after the film had long worn out its welcome, the furor surrounding the existence of snuff cinema endured. This cinematic bogeyman has inspired innumerable films and books, and has become so entrenched in America’s psyche that even today concerned citizens cite snuff as being a billion-dollar industry lurking just beneath the radar of the law. Despite countless, concerted efforts to unearth a bona fide snuff film, authorities have resigned this cinematic phenomenon—as defined by the film that inspired the concept--to the domain of urban legends.

So what is a snuff film? The Random House Dictionary, in a relatively new entry, defines a snuff movie as “a pornographic film that shows an actual murder of one of the performers, as at the end of a sadistic act.” It also states in a secondary definition that “snuff films” are synonymous with “splatter films,” an egregious error in and of itself. The American Heritage Dictionary offers a similarly erroneous definition, sans the splatter film connection. For reasons of clarity and propriety, a proper definition of snuff should instead be based on the film that single-handedly popularized the concept and introduced it into the public lexicon:

Snuff film (noun) Any film that depicts the premeditated onscreen death of one or more of its actors without their knowledge or consent, which is produced specifically for the sole intention of profiting from its distribution.

Although the film in question may be pornographic, this has never been part of the essential criteria as some references cite, as the film which defines snuff is not sexually explicit. Furthermore, profit is the ultimate objective. An exorbitant price tag compensates for the extremely limited distribution through black market channels, willingly paid for by affluent clients with jaded interests. Finally, “splatter films” are legitimate, perfectly legal productions that rely on staged bloodletting for scenes of gratuitous violence, leaving no room for association with snuff, which eschews the use of special effects by actually sacrificing its cast. (Most modern horror films contain a certain amount of gratuity, so the cinematic use of the term “splatter” has become virtually obsolete except in a historical context.)

There are other types of cinema that are often associated--or even conflated--with snuff films, despite the fact that they fall short of the necessary criteria. The most popular of these is known as the “shockumentary,” a brand of sensational, exploitive pseudo-documentary that often collects “found” footage of death and dismemberment from other sources, including newsreels or home video recordings that unintentionally capture such shocking images. (Often, these tasteless productions—such as the infamous Faces of Death series--pad out these scraps of genuine carnage with special effects-laden “fakes” and cruel scenes of real-life animal butchery.) Although this type of “entertainment” has played grindhouses since the 1930s, they became prominent fixtures at drive-ins throughout the 1960s and 1970s thanks to an Italian production released worldwide as Mondo Cane [A Dog’s Life] (1962). (Because of this film’s box-office success, and the slough of similarly titled films in its wake, shockumentaries are also referred to as “mondo” films.) Since shockumentaries occasionally depict real scenes of death—even though they weren’t specifically produced for the film and with criminal intent—their popularity seems to give snuff films validity by showing that there very well could be a demand for such sadistic fare, however limited.

Another misconception is that video recordings made by serial killers for the sole purpose of documenting their disturbing deeds qualify as snuff. On the contrary, these films—known as “trophy” films, with which the psychopathic personality can use to relive the moments of their sadistic crimes—are never made with a financial gain in mind, so they are considered by criminologists a separate animal altogether.

Most people are aghast when they first learn about snuff films, and may ask, “How could somebody do such a thing? What is being done to bring to justice those individuals responsible these black market atrocities?” Truth be told, very little is being done about them, simply because there is no evidence that they even exist. Not to say that such a thing as a snuff film isn’t possible. Still, when one takes into account the complicated logistics of creating and distributing such a product, along with the lack of verifiable proof that any such film has ever been produced and sold, snuff films—as defined above—are improbable. So why has so much fuss been made about snuff films, if their very existence has never been confirmed? Historians can lay the blame entirely at the feet of the aforementioned film Snuff.

In 1972, film producer Allan Shackleton bought the world distribution rights to a low budget film called The Slaughter (1971). Made by sexploitation filmmakers Michael and Roberta Findlay, this thinly veiled take on the Manson family’s well-publicized killing spree had a limited theatrical release before being shelved due to poor box-office returns. Shackleton desperately needed a creative approach with which to market the film successfully, so he decided that the best publicity he could muster was through controversy.

In 1975, Shackleton put together a guerilla cast and crew with which to shoot a new five-minute finale. This new footage depicted what is supposed to be one of the original actresses in a candid moment following the final take. After she makes time with the purported director of the film, the remaining crew members descend upon her with cameras rolling, capturing her alleged final moments. The viewer is forced to watch as the demented filmmaker tortures and eventually eviscerates the unwary thespian, conveniently completing his unholy mission only seconds before the camera runs out of film stock. Anyone who has seen this footage remains unconvinced by the dubious proceedings: There is no continuity whatsoever between the two films, the performances are poor, and the dimestore special effects even worse. But this didn’t deter Shackleton, as the whole point was to get ticket buyers into the theatre; whatever happened after that was immaterial. Even the opportunistic director, though, didn’t realize the impact his deception would have on this country… and this is where snuff went from being an obscure concept to a nationwide panic and an indefatigable urban legend.

Bearing a new title alongside ambiguous claims that it was “The Picture They Said Could Never Be Shown,” press releases and advertisements implied that, unlike other horror films, the carnage caught on camera was not faked. Shackleton then proceeded to distribute bogus newspaper clippings detailing the efforts of one “Vincent Sheehan,” the head of a fictional organization called Citizens for Decency, and his relentless crusade against the film in question. Not surprisingly, genuine groups bought into the prefabricated hysteria, and before long every theatre showing the film was festooned with picket lines protesting the public display of what they assumed to be a real-life atrocity. Almost overnight, this threadbare production made national headlines, whilst establishing the groundwork for a myth that still persists to this very day.

Within a few months of its controversial release, authorities looked into the possible illegality of the film, but found the content so laughable as to not warrant any further investigation. Surprisingly, their official statements exposing the rumors to be false did not deter the public outcry, as word of mouth continued, perpetuated by individuals who had never even seen the film, or questioned its authenticity. Even after the film had long worn out its welcome, the furor surrounding the existence of snuff cinema endured. This cinematic bogeyman has inspired innumerable films and books, and has become so entrenched in America’s psyche that even today concerned citizens cite snuff as being a billion-dollar industry lurking just beneath the radar of the law. Despite countless, concerted efforts to unearth a bona fide snuff film, authorities have resigned this cinematic phenomenon—as defined by the film that inspired the concept--to the domain of urban legends.

Preface to

The Satanic Conspiracy: Witch Hunting in the

Twentieth Century and Beyond

This—the last of my Major Writing Assignments for English 098—was the most daunting of the three projects. Researching the piece was not difficult, but it was extremely time consuming nonetheless, and the collection of citations became an endeavor unto itself. Despite the fact that I would have liked more time (and space) to discuss the issues of Satanic ritual abuse and religious intolerance, I am very pleased with the end product. I feel I argued my point well, and offered sufficient reasons to support my thesis statement. I presented strong quotes from an array of respected authorities, many of whom aren’t professed Satanists, thus avoiding any accusations of using only biased sources. The overall writing of this piece is stronger than the previous two, as I took into careful consideration the feedback I received about certain stylistic tendencies I may at times display. (The abundance of run-on sentences was amongst the biggest gripes made by both my advisor and my peers, so I hope that this last essay was far less migraine-inducing than my previous assignments.) One of my main concerns when writing this piece was that it not be reiterative of my previous essay, “Snuff: The Final Cut.” Both dealt with debunking an urban legend, so it would have been easy (and tempting) to simply follow the same formula. Luckily, I feel I was successful in restructuring it in a way so readers wouldn’t be hampered too terribly much by feelings of déjà vu.

I chose the subject “The Satanic Conspiracy: Witch Hunting in the Twentieth Century and Beyond” in order to further discredit the myths involving Satanic cults and their supposed involvement in abuse and murder in the last forty-odd years. In addition, I wanted to clarify what Satanism is and how its ideologies contradict the unfounded rumors that have been constantly leveled against it by the religious right. Having been a card-carrying member and an active representative of the Church of Satan for about ten years now, I have been exposed to no shortage of prejudice and bigotry when I have disclosed my philosophical beliefs in public. Since I knew my audience probably knew very little if anything about Satanism, I felt it would be a perfect opportunity to shed some light on the subject. Furthermore, I felt it would interest most readers because of its sensationalistic aspects, even if they did not agree with the assessment I made.

I chose the subject “The Satanic Conspiracy: Witch Hunting in the Twentieth Century and Beyond” in order to further discredit the myths involving Satanic cults and their supposed involvement in abuse and murder in the last forty-odd years. In addition, I wanted to clarify what Satanism is and how its ideologies contradict the unfounded rumors that have been constantly leveled against it by the religious right. Having been a card-carrying member and an active representative of the Church of Satan for about ten years now, I have been exposed to no shortage of prejudice and bigotry when I have disclosed my philosophical beliefs in public. Since I knew my audience probably knew very little if anything about Satanism, I felt it would be a perfect opportunity to shed some light on the subject. Furthermore, I felt it would interest most readers because of its sensationalistic aspects, even if they did not agree with the assessment I made.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

+One-Sheet.jpg)

+One-Sheet.jpg)

+One-Sheet.jpg)